For some time now, we’ve seen regular changes to the way we can combat illnesses such as cancer. Despite being one of the leading causes of death worldwide, overcoming something as powerful as cancer takes a huge amount of innovation and, in some cases, luck. However, thanks to the combined planning of SWRI and UTSA, we could see a major shift in battling cancer thanks to the development of a 3D-printed medical implant.

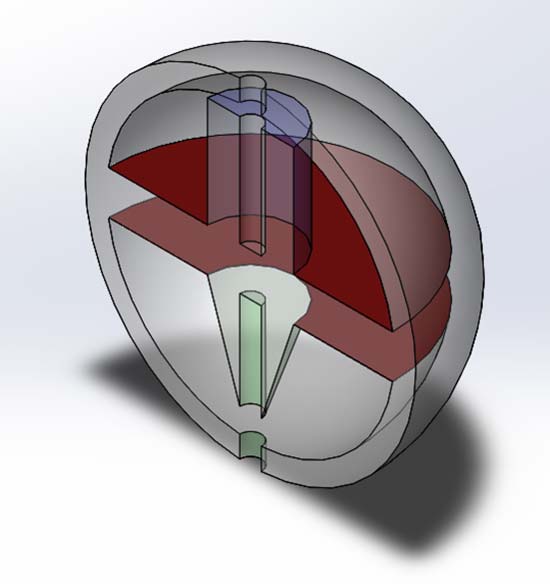

The researchers at both the Southwest Research Institute and The University of Texas at San Antonio have produced some hugely impressive 3D implants. The device, it is hoped, could be used to provide ailments to patients who are suffering from long-term conditions such as cancer, or even arthritis.

Albert Zwiener, the Project Co-Leader, said: “The implant addresses a specific patient’s illness in addition to their medical history and other health issues. We inject this non-invasive device into the body to deliver medicine over a significant period of time.”

For anyone undertaking drugs to deal with a health condition, they must take an amount that is built for their specific condition. However, those who need to take a specific dosage often need to do so with the help of a doctor or medical professional. With this solution, that need could be automated, with the exact amounts produced and used as needed during the day for the right dosage.

At the moment, the project is backed by the Connect program, which has invested around $125,000 into the project. The main objective is to support projects like this, as well as better enable proposals for peer reviewed research in the future.

A transformative step forward

The aim is to create the device using a specific 3D printer over at the UTSA grounds, that can be used to print our biodegradable material. Once treatment is finished, then, the little implant would dissolve naturally, further reducing the need for medical appointments to get it removed.

Also, it will be used to help work with localized immunotherapy, which will be used to help combat cancerous tumours. However, while this is being mostly marketed as a cancer combatant, the belief is that it will be able to provide access to just about any drug.

According to the other Co-Leader, Lyle Hood: “If clinically translated, this would allow for doctors and pharmacists to print specific dosages to meet patients’ needs. In immunotherapy, most strategies employ systemic circulation through an iv line, much like chemotherapy. This can cause issues with immune reactions far away from the intended target. We hope that by delivering locally, we can keep acute effects constrained to the diseased region.”

This comes as part of a growing wave of technology of this kind, producing hope that, in the long-term, we can make progressive adjustments to how we treat and handle illness.